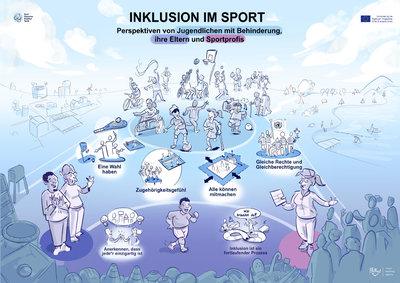

The Sport Empowers Disabled Youth 2 (SEDY2) project encourages inclusion and equal opportunities in sport for youth with a disability by raising their sports and exercise participation in inclusive settings. It was important to ensure that the authentic views, wishes and feelings of youth with a disability regarding inclusion in sport were attained. Therefore, online focus groups were conducted with youth with a disability, their parents and sport professionals in Finland, Lithuania, Portugal and The Netherlands. Seven themes regarding inclusion in sport have been identified from these interviews: having a choice, sense of belonging, everyone can participate, same rights and equality, acknowledge that everyone is unique, inclusion is an ongoing process and terminology (language) is challenging.

DOCUMENT

The Sport Empowers Disabled Youth 2 (SEDY2) project encourages inclusion and equal opportunities in sport for youth with a disability by raising their sports and exercise participation in inclusive settings. It was important to ensure that the authentic views, wishes and feelings of youth with a disability regarding inclusion in sport were attained. Therefore, online focus groups were conducted with youth with a disability, their parents and sport professionals in Finland, Lithuania, Portugal and The Netherlands. During the online EUCAPA 2020 conference the preliminary results of these focus groups were presented.

DOCUMENT

During the online International Symposium of Adapted Physical Activity (ISAPA) in June 2021 te results of the SEDY2 project were presented. Aim The Erasmus+ Sport Empowers Disabled Youth 2 (SEDY 2) project addresses the topic of encouraging inclusion and equal opportunities in sport. Currently, different terminology about inclusion is being used in different countries, making it difficult to compare findings and to set unilineal goals and targets. In order to tackle the issues that are currently preventing youth with disabilities from participating in sports, the primary purpose of this study is to reach a consensus statement on what inclusive sport truly means. Literature shows that inclusion is a question about individual choice of a sporting activity across a continuum of segregated, integrated and inclusive approaches (Kiuppis, 2018) considered as The inclusion spectrum (Stevenson & Black, 2011). Most of the existing research is not based on the authentic wishes and feelings of children and young people with a disability themselves. Therefore, the main research question is ‘Inclusion in sport: what does it mean in practice?’ Methods To ensure that the authentic views, wishes and feelings regarding inclusion in sport were attained, online focus groups interviews were conducted with children and young people with a disability, their parents and sport professionals in Finland, Lithuania, Portugal and The Netherlands. Data is coded and analysed with Maxqda through the method of thematic content analysis. Results All four countries conducted a focus group with each stakeholder group: children with a disability themselves, their parents and sport professionals. In total 12 focus group interviews were conducted. Preliminary results show that inclusion is about individual needs and wishes and is associated with terms as feeling welcome, taking part, having a choice and equal opportunity. “…it is equal opportunities for all to participate and that, that you are part of like a group and, and that feeling of being part of a group and that you feel welcome.” Focus groups with professionals found that for them inclusion is not the same as inclusion policy. “I think we are talking about the same thing, and we feel the same way, but if we compare that to the inclusion policy or the sports covenant, maybe we are not always talking about the same thing.” All focus groups will be analysed and the results will be presented during the session. Discussion/conclusion Results have been discussed within the SEDY project group with sport organisations, Paralympic Committees and Universities of Applied Sciences to reach internal consensus. In order to tackle the issues that are currently preventing people with disabilities from participating in sports, there is need to reach a broad consensus statement on what inclusive sport truly means. Therefore the next is to discuss the results externally, to reach broad consensus. This can be taken as starting point for actual steps of improvement to include more children with disabilities in sport.

YOUTUBE

The Sport Empowers Disabled Youth 2 (SEDY2) project encourages inclusion and equal opportunities in sport for youth with a disability by raising their sports and exercise participation in inclusive settings. The SEDY2 Inclusion Handbook is aimed at anybody involved in running or working in a sport club, such as a volunteer, a coach, or a club member. The goal of the handbook is to facilitate disability inclusion among mainstream sport providers by sharing SEDY2 project partners’ best practices and inclusive ideas.

DOCUMENT

Es war wichtig, die authentischen Ansichten, Wünsche und Empfindungen von Jugendlichen mit Behinderung in Bezug auf Inklusion im Sport zu erhalten. Daher wurden Online-Fokusgruppen mit Kindern und Jugendlichen mit einer Behinderung, ihren Eltern und Expert*innen im Sportbereich in Finnland, Litauen, Portugal und den Niederlanden durchgeführt. Aus diesen Interviews wurden sieben Themen bezüglich Inklusion im Sport identifiziert, die im Folgenden einzeln erläutert werden.

DOCUMENT

Background: Little evidence is available about how sports participation influences psychosocial health and quality of life in children and adolescents with a disability or chronic disease. Therefore, the aim of the current study is to assess the association of sports participation with psychosocial health and with quality of life, among children and adolescents with a disability. Methods: In a cross-sectional study, 195 children and adolescents with physical disabilities or chronic diseases (11% cardiovascular, 5% pulmonary, 8% metabolic, 8% musculoskeletal/orthopaedic, 52% neuromuscular and 9% immunological diseases and 1% with cancer), aged 10–19 years, completed questionnaires to assess sports participation, health-related quality of life (DCGM-37), self-perceptions and global self-worth (SPPC or SPPA) and exercise self-efficacy. Results: Regression analyses showed that those who reported to participate in sports at least twice a week had more beneficial scores on the various indicators compared to their peers who did not participate in sport or less than twice a week. Those participating in sports scored better on all scales of the DCGM-37 scale, on the scales for feelings of athletic competence and children but not adolescents participating in sports reported greater social acceptance. Finally, we found a strong association between sport participation and exercise self-efficacy. Conclusions: This study provides the first indications that participating in sports is beneficial for psychosocial health among children and adolescents with a disability. However, more insight is needed in the direction of the relationships.

DOCUMENT

Description: The Neck Pain and Disability Scale (NPDS or NPAD) is a questionnaire aiming to quantify neck pain and disability.1 It is a patient-reported outcome measure for patients with any type of neck pain, of any duration, with or without injury.1,2 It consists of 20 items: three related to pain intensity, four related to emotion and cognition, four related to mobility of the neck, eight related to activity limitations and participation restrictions and one on medication.1,3 Patients respond to each item on a 0 to 5 visual analogue scale of 10 cm. There is also a nine-item short version.4 Feasibility: The NPDS is published and available online (https://mountainphysiotherapy.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/Neck-Pain-and-Disability-Scale.pdf).1 The NPDS is an easy to use questionnaire that can be completed within 5 to 8 minutes.1,5 There is no training needed to administer the instrument but its validity is compromised if the questionnaire must be read to the patient.2 Higher scores indicate higher severity (0 for normal functioning to 5 for the worst possible situation ‘your’ pain problem has caused you).2 The total score is the sum of scores on the 20 items (0 to 100).1 The maximum acceptable number of missing answers is three (15%).4 Two studies found a minimum important change of 10 points (sensitivity 0.93; specificity 0.83) and 11.5 points (sensibility 0.74; specificity 0.70), respectively.6,7 The NPDS is available in English, Dutch, Finnish, French, German, Italian, Hindi, Iranian, Korean, Turkish, Japanese and Thai. Reliability and validity: Two systematic reviews have evaluated the clinimetric properties of 11 of the translated versions.5,8 The Finnish, German and Italian translations were particularly recommended for use in clinical practice. Face validity was established and content validity was confirmed by an adequate reflection of all aspects of neck pain and disability.1,8 Regarding structural validity, the NPDS is a multidimensional scale, with moderate evidence that the NPDS has a three-factor structure (with explained variance ranging from 63 to 78%): neck dysfunction related to general activities; neck pain and neck-specific function; and cognitive-emotional-behavioural functioning. 4,5,9 A recent overview of four systematic reviews found moderate-quality evidence of high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alphas ranging from 0.86 to 0.93 for the various factors).10 Excellent test-retest reliability was found (ICC of 0.97); however, the studies were considered to be of low quality.3,10 Construct validity (hypotheses-testing) seems adequate when the NPDS is compared with the Neck Disability Index and the Global Assessment of Change with moderate to strong correlations (r = 0.52 to 0.86), based on limited moderate-quality studies.3,11,12 One systematic review reported good responsiveness to change in patients (r = 0.59).12

DOCUMENT

Sport is associated with physical well-being and social well-being and it is crucial to understand that it is a right to have access and participate in sport. It’s a question about individual choice of a sporting activity across a continuum of segregated, integrated and inclusive approaches (Kuippis, 2018). Considered as The inclusion spectrum (Stevenson & Black, 2011). The inclusion debates in sport are not about how to substitute special structures with integrative ones, and those in turn with inclusive ones, but are characterized by giving each approach equal importance and validity (Kuippis, 2018). The Social Ecological Model for Health Promotion provides a useful framework for understanding how various sectors influence participation in physical activity or sport (McLeroy, Bibeau, Steckler, & Glanz, 1988). In SEDY 2 we conducted focusgroups with young people with disabilities, their parents/caretakers and professionals in four different European countries (Finland, Portugal, Lithuania and The Netherlands). In the focus groups we want to ask people involved on their view on Inclusion in sport in practice. What does it mean for them and are we hearing the voices of young people with a disability?

MULTIFILE

Objective: To investigate the effects of a school-based once-a-week sports program on physical fitness, physical activity, and cardiometabolic health in children and adolescents with a physical disability. Methods: This controlled clinical trial included 71 children and adolescents from four schools for special education [mean age 13.7 (2.9) years, range 8–19, 55% boys]. Participants had various chronic health conditions including cerebral palsy (37%), other neuromuscular (44%), metabolic (8%), musculoskeletal (7%), and cardiovascular (4%) disorders. Before recruitment and based on the presence of school-based sports, schools were assigned as sport or control group. School-based sports were initiated and provided by motivated experienced physical educators. The sport group (n = 31) participated in a once-a-week school-based sports program for 6 months, which included team sports. The control group (n = 40) followed the regular curriculum. Anaerobic performance was assessed by the Muscle Power Sprint Test. Secondary outcome measures included aerobic performance, VO2 peak, strength, physical activity, blood pressure, arterial stiffness, body composition, and the metabolic profile. Results: A significant improvement of 16% in favor of the sport group was found for anaerobic performance (p = 0.003). In addition, the sport group lost 2.8% more fat mass compared to the control group (p = 0.007). No changes were found for aerobic performance, VO2 peak, physical activity, blood pressure, arterial stiffness, and the metabolic profile. Conclusion: Anaerobic performance and fat mass improved following a school-based sports program. These effects are promising for long-term fitness and health promotion, because sports sessions at school eliminate certain barriers for sports participation and adding a once-a-week sports session showed already positive effects for 6 months.

DOCUMENT

Presentatie over de kracht van aangepaste sport voor de gemeente Zaanstad

DOCUMENT