Dasha Ilina’s video work Advice Well Taken: Folk Tales of Digital Savation uses the ‘techlore’ concept to find out what ‘urban legends’ are in the age of smartphones. You can watch the ‘director’s cut’ of the video installation here. You can also have a look at a selection of the catalogue here. The 2023 Impakt Festival information about the installation can be found here. The essay was commissioned by Dasha Iina for the catalogue that came out in November 2023 during the Impakt Festival in Utrecht, where the video installation premiered. Read the ‘cookie conversation’ with the artist here, conducted by the Impakt Festival.

MULTIFILE

Een schoone ende wonderlijcke prognosticate (1560) is one of many Dutch texts dealing with the trickster Till Eulenspiegel, known as "Tijl Uilenspiegel" in the Low Countries and "Owlglass" in England. The poem differs from most Eulenspiegel literature in two key respects. First, it treats the figure as a narrator rather than a character, and second, it seems designed for performance rather than simple recital. We offer here an English translation of this remarkable piece, lightly annotated throughout.

DOCUMENT

Report on the current state of affairs on ethnomusicology in the Netherlands for international association ICTM

DOCUMENT

In Nederland komen maandelijks mensen in vertelgroepen bij elkaar om samen de kunst van het verhalen vertellen te beoefenen. Tekla Slangen liep een half jaar als participerend onderzoeker mee met een lokale vertelgroep. In dit artikel geeft ze een inkijk in wat vertellers beweegt en waaraan ze hun waarde ontlenen.Lang voordat Netflix ons elke dag duizend en een verhalen kon vertellen via een beeldscherm, waren er mensen die de mooiste verhalen in geuren en kleuren uit de doeken deden en hun publiek van alles lieten beleven:verhalenvertellers.Heden ten dage zijn er in Nederland nog steeds tal van vertellers en vertelgroepen actief die voor groot en klein publiek optreden. Zij vertellen uit het hoofd allerlei soorten verhalen, van sprookjes, mythes en fabels tot fragmenten uit de geschiedenis en persoonlijke ervaringen. Wat is de aantrekkingskracht van het verhalen vertellen voor de individuele verteller? Wat voor activiteiten ondernemen zij? En wanneer vinden ze het vertellen van een verhaal echt geslaagd? Deze vragen zijn de aanleiding geweest voor een kleinschalig etnografisch onderzoek naar vertellers bij een vertelgroep. In dit artikel beschrijf ik de belangrijkste resultaten, met de Nederlandse vertelscene als kader.

DOCUMENT

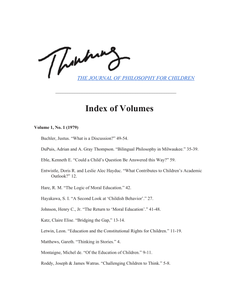

The journal was a forum for the work of both theorists and practitioners of philosophical practice with children, and published such work in all forms, including philosophical argument and reflection, classroom transcripts, curricula, empirical research, and reports from the field. The journal also maintained a tradition in publishing articles in the hermeneutics of childhood, a field of intersecting disciplines including cultural studies, social history, philosophy, art, literature and psychoanalysis.

DOCUMENT

This chapter addresses environmental education as an important subject of anthropological inquiry and demonstrates how ethnographic research can contribute to our understanding of environmental learning both in formal and informal settings. Anthropology of environmental education is rich in ethnographies of indigenous knowledge of plants and animals, as well as emotional and religious engagement with nature passed on through generations. Aside from these ethnographies of informal environmental education, anthropological studies can offer a critical reflection on the formal practice of education, especially as it is linked to development in non-Western countries. Ethnographic and critical studies of environmental education will be discussed as one of the most challenging directions of environmental anthropology of the future. This is an Accepted Manuscript of a book chapter published by Routledge/CRC Press in "Environmental Anthropology: Future Directions" on 7/18/13 available online: https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203403341 LinkedIn: https://www.linkedin.com/in/helenkopnina/

MULTIFILE

De vraag wat Bourgondische letterkunde is, is niet eenduidig te beantwoorden daar ruimte en tijd van invloed zijn op de definitie.

DOCUMENT

The current transnational climate (British Council, 2014) in Europe is likely to continue to generate institutional and classroom situations which dictate that difference and otherness be the norm rather than the exception. Unfortunately, in the 1960's, Black and minority ethnic (BME) migrants from the former British colonies had less-than-favorable educational experiences in Britain due to prejudice and stereotyping mainly arising from cultural differences. Since then there have been a plethora of studies, policies, and reports regarding the perpetuation of discrimination in educational institutions. Today, British higher educational institutions have finally begun to recognize the need to reduce progression and attainment gaps. However, their focus tends to only consider the student “Black and Minority Ethnic attainment gap” with almost no attention being given to educators', or more specifically there is a distinctive lack of thought given to the female BME educators' progression and attainment in British HEIs. As such, this paper draws theoretically and conceptually on critical cultural autoethnography, to illustrate the value of conducting research into a female's BME educators' personal and professional experiences, and “gives voice to previously silenced and marginalized experiences” (Boylorn and Orbe, 2014, p. 15). In doing so, I highlight how higher educational institutions underutilisation of such competencies and contributions have and continue to perpetuate BME underachievement. I conclude the paper by questioning the accountability of providing support for BME educators progression and attainment, challenge educational leaders to consider the value and utilization of cultural knowledge, and implore all educators to reflect on how their personal experiences influence their professional identity.

MULTIFILE